Impact of public engagement

Sea level rise, and how not to drown in the facts

It’s time to dive a bit more deeply (pun intended) into my project, specifically the topic of sea level rise. You’ve obviously heard of it, but what are the facts and figures, and why is it so important?

It’s happening

As you may be aware, we will unavoidably have to deal with some amount of sea level rise: at least 4 mm per year globally (Le Cozannet et al., 2022), and perhaps much more. And it’s not just something of the future: worldwide sea levels have already risen by about 20 cm over the course of the 20th century. We’ll likely reach the next 20 cm of sea level rise between 2025 and 2070, and another 20 cm on top of that between 2050 and 2100. At first sight that doesn’t seem too much of a problem: our dikes should be high enough for a few dozen centimetres of sea level rise, right? However, even at that scale we’ll see increased chances of flooding, both from the sea and from rivers, and a myriad of other problems, like soil salinisation (bodemverzilting) and damage to wooden house foundations.

Looking further ahead, even if we manage to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, global sea level rise will likely reach 1 metre between the year 2150 and 2350. If emissions aren’t reduced at all, we will reach this point much earlier: between 2090 and 2140 (KNMI Klimaatsignaal’21, 2021). And it’s not just overall sea level rise that will change our lives: extreme weather events such as storms and floods are increasing as well. For example, damaging floods in the Pacific that now occur every 20 to 25 years, are projected to occur each year by the middle of this century (Le Cozannet et al., 2022).

Looking further ahead, even if we manage to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, global sea level rise will likely reach 1 metre between the year 2150 and 2350. If emissions aren’t reduced at all, we will reach this point much earlier: between 2090 and 2140 (KNMI Klimaatsignaal’21, 2021). And it’s not just overall sea level rise that will change our lives: extreme weather events such as storms and floods are increasing as well. For example, damaging floods in the Pacific that now occur every 20 to 25 years, are projected to occur each year by the middle of this century (Le Cozannet et al., 2022).

On top of these predictions, there’s a lot of uncertainty about the future of the large ice sheets of Greenland and West-Antarctica. Even when global temperature rise stays within the Paris Agreement range of 1.5 to 2 °C above pre-industrial levels, we will still cross several climate tipping points, including irreversible instability of the Greenland and West-Antarctic ice sheets. As for a worst case scenario: if global warming continues to be over 5 °C for several centuries, the East-Antarctic Ice Sheet will collapse, causing about 55 metres of sea level rise (Armstrong McKay et al., 2022).

Less (warming) is more (better)

So, after having read all those unsettling predictions, take a moment to ask yourself what you feel right now. Do you feel a sense of panic? Hopelessness? A sinking feeling (again, pun intended)? A sudden urge to install solar panels, or to move to a house on top of a mountain? Or do you feel emotionally disconnected because it’s just a bunch of numbers? Whatever you’re feeling right now, please continue reading, because I’ve got a hopeful insight for you: what we do today matters for the future. Even with all those tipping points it’s important to realise that less warming is always better.

Let’s take a little trip into the future. I’d like to ask you to take a moment to imagine yourself in the year 2080. How old will you be? How about your children, or your nieces and nephews? I might just make it at 97 years old, and hopefully the coming decades will bring enough medical advances that my partner and I will still be relatively healthy at that age. Perhaps our nieces and nephews will visit us every now and then, although at around 60 years old they’ll probably be busy enough with their own lives.

Now let’s talk about sea levels in the year 2080. You may have read something before about the different IPCC socioeconomic scenarios, varying from SSP1, in which greenhouse gas emissions are very low, to very high emissions in SSP5. According to the IPCC WG1 Interactive Atlas (which is pretty fun to play with, so give it a go), these different scenarios present a clear difference for what the world will look like in the future. The ‘time series’ graph for the regions Northern Europe, Western and Central Europe gives us 30 cm sea level rise in SSP1, 35 cm in SSP2, 40 cm in SSP3, and 45 cm in SSP5.

Now let’s talk about sea levels in the year 2080. You may have read something before about the different IPCC socioeconomic scenarios, varying from SSP1, in which greenhouse gas emissions are very low, to very high emissions in SSP5. According to the IPCC WG1 Interactive Atlas (which is pretty fun to play with, so give it a go), these different scenarios present a clear difference for what the world will look like in the future. The ‘time series’ graph for the regions Northern Europe, Western and Central Europe gives us 30 cm sea level rise in SSP1, 35 cm in SSP2, 40 cm in SSP3, and 45 cm in SSP5.

Sure, the difference between 30 and 45 cm doesn’t seem very big. But did you know that our Oosterscheldekering, the largest of the Delta Works that protect the Netherlands from North Sea floods, is useful up to 35 centimeters of sea level rise (Deltanieuws 03, 2017)? That means that depending on which emissions scenario we choose to take, in the year 2080 we may or may not still be properly protected by the Oosterscheldekering. So perhaps we shouldn’t wait too long to join the waitlist for a retirement home that will still be safe from flooding at that point…

What do people know, think, and feel about sea level rise?

Having said all that, let’s travel back to the present. As we’ve seen earlier in this research notebook, only communicating about facts is not very effective. So now that we have some of the facts down, let’s talk about feelings. What do citizens in general know, think and feel about sea level rise?

Even though 72% of the Dutch indicate that they’re worried about climate change in general (Kaal & Damhuis, 2020), I’ve found no recent studies on how the Dutch public feel specifically about sea level rise. Given the rapid pace of change in the realm of climate change, any research on this topic that’s older than a few years has already lost much of its relevance.

Even though 72% of the Dutch indicate that they’re worried about climate change in general (Kaal & Damhuis, 2020), I’ve found no recent studies on how the Dutch public feel specifically about sea level rise. Given the rapid pace of change in the realm of climate change, any research on this topic that’s older than a few years has already lost much of its relevance.

And extrapolating from other countries doesn’t necessarily make a lot of sense either. I don’t think I’m exaggerating if I say that we, the Dutch, have our own special symbiotic relationship with the sea: our history, present and future are significantly shaped by our geographic location as, essentially, inhabitants of a river delta. We’ve got more than 17,000 km of retaining dikes to keep us safe (Waterschappen.nl, 2015). Our Delta Works have been dubbed one of the seven wonders of the modern world. We know what the sea can do, both the good and the bad. And much like lion tamers, we’re proud of having this dangerous beast under control and even using it to our benefit – though we should be cautious of getting complacent or even overconfident.

For lack of Netherlands-specific data, I will briefly touch upon a number of studies done in other countries. Australians tend to view climate change as ‘psychologically distant’ (Jones et al., 2017): distant in time (far in the future), socially distant (happening to other people), geographically distant (happening far away), and uncertain. New Zealanders tend to have quite accurate ideas of current sea level rise predictions, but when asked about worst-case scenarios, they grossly overestimate what is seen as scientifically plausible (Priestley et al., 2021). About half of Americans (52%) are worried about rising sea levels, which is quite a lot less than the amount of people worried about droughts (75%), extreme heat (74%) and water shortages (72%), for instance (Leiserowitz et al., 2022). And in a study in the UK, about two-thirds of participants indicated that they were concerned about sea level rise, even though only about one-third saw themselves as well-informed on the topic (Chilvers, 2014).

…and what would I like them to know, think, and feel?

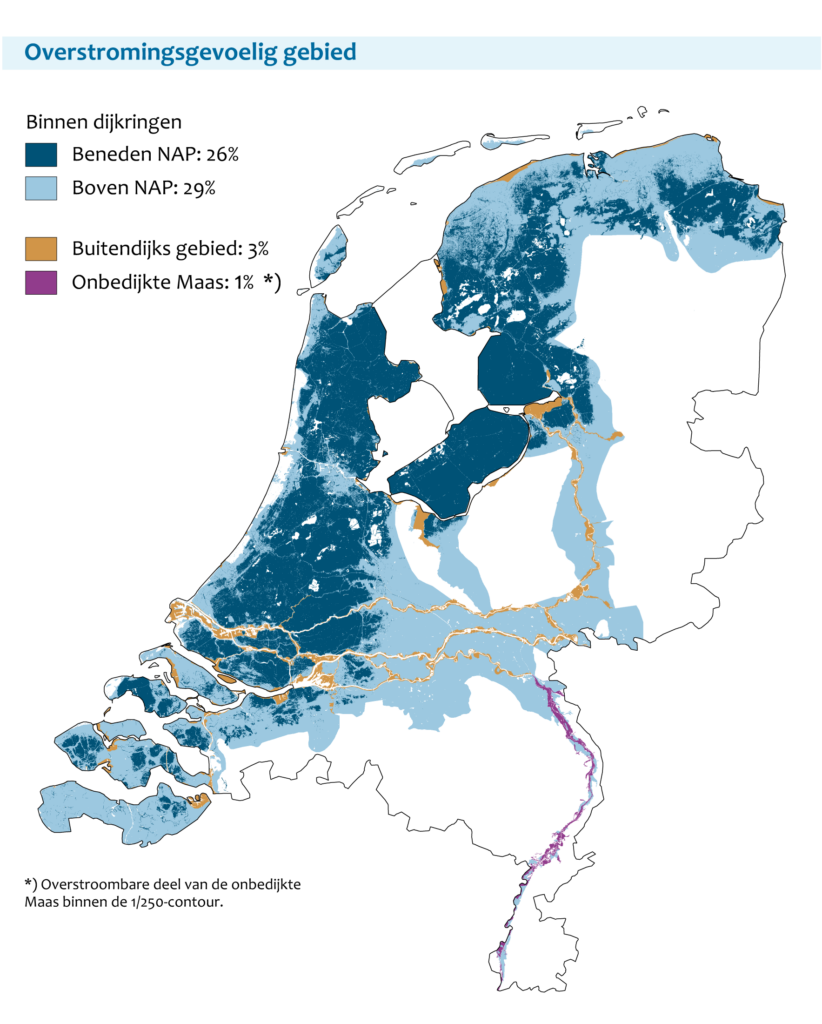

Zooming back in to the Netherlands, sea level rise is undeniably important to the country. Currently, 26% of the country’s land surface is below sea level (dark blue in the image below), and another 29% is above sea level but still prone to flooding (light blue). Adding another 4% located outside dike rings (orange + purple), we come to a whopping 59% of the country’s land surface that is prone or sensitive to flooding (PBL, 2019):

(text continues after image)

Combining that with the IPCC predictions and our little trip into the future, it’s clear that sea level rise is relevant for us, and what we do is relevant for sea level rise. That’s what I’d like more people to realise.

In my next entries, I’ll get more specific and concrete about the audiences I will try to reach with my public engagement activities, the impact I would like to make on them and how I’m hoping to do that.

Back to you

Having read all this, how do you feel about sea level rise? And how do you think other people feel about it? Do you ever talk about it in your daily life or does it feel as psychologically distant as it does for many other people? And if you could change anything about other people’s thoughts and feelings about sea level rise, what would it be?

I think your last picture makes it very ‘real’ for many people. I felt like wanting to check if the place where I live is light blue or white. I vaguely remember that Geo Science or another institute or organization had a tool for this (to check per village/ city what the effects would be). Makes it very ‘dicht bij huis’….